October 17, 2021

30 Years Since Huib Drion wrote his Letter

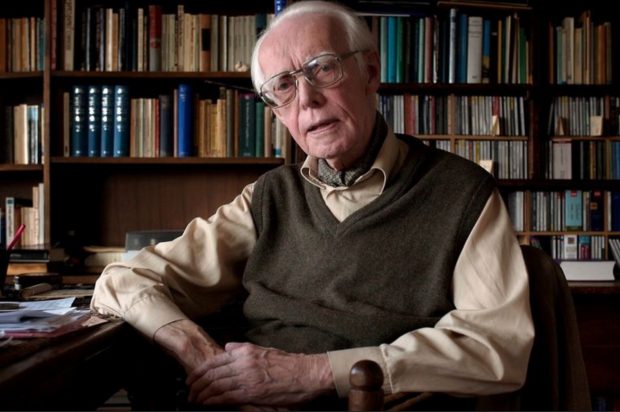

30 Years Since Huib Drion wrote his Letter that it is ‘The right of older people to decide for themselves’

See Huib Drion – NRC, 19 October 1991

Dutch Title: ‘Het zelfgewilde einde van oudere mensen’

There is no doubt in my mind that many old people would find great peace of mind if they had a means at their disposal to end life in an acceptable manner at a moment that is appropriate to them.

So said the former Vice President of the Dutch Supreme Court Huib Drion in a Letter to the Editor on October 19, 1991.

Of the right of older people to decide for themselves, Professor Drion wrote:

Of course, our society already provides many means by which people can end their lives: there are trains that you can throw yourself into, there are buildings that you can fall down from, there are canals and rivers to drown yourself in, there is rope one can buy and I’ll leave it at that.

But these are not very attractive means: neither for those who have to use them, nor for those around them and for society as a whole.

Some members of our society may have more acceptable means: take doctors and pharmacists for example.

But for the majority of people, such means are not available. Their only hope is travel to a distant land in the hope that, more or less surreptitiously, they will succeed in obtaining the substances needed.

That’s pretty much the current situation. What is it that maintains this situation as acceptable?

So as far as society is concerned, most people are denied the means by which they can end their lives in a not too repulsive way.

My question however is whether such a policy that makes the act of suicide as abhorrent as possible can be argued can be justified?

What for the old man who thinks he has lived long enough and who dreads a future life of continual decay?

I do know: the division between old and not-so-old is not a sharp one.

Those who are 20 will draw the line between old and not-so-old differently to a 75-year-old.

But that does not alter the fact that a person who ends his life at the age of 75 can, in general, know better what kind of life he risks cutting short far more than a twenty-year-old.

The medical problem – that is those who are seriously ill – receive a lot of attention in discussion of the euthanasia problem than those who are old.

The great, usually unexpressed, concern of many old people, however, is that there will come a time for them when they will no longer be able to take care of themselves in the most basic things of life, due to physical and or mental deterioration.

Removing that fear, as much as is possible, seems to me to be an essential obligation for a society in which the number of old people is increasing.

This obligation will not be met by merely providing care and nursing for old people who can no longer take care of themselves.

The provision of such care is, of course, essential, but it is not sufficient. A care home is far from a satisfactory solution for those who do not want to live a life being cared for by others.

To say that these people must jump into the water or jump off a block of flats or buy a rope, if they want to end their life, serves no one and nothing, not even the sanctity of life.

People never say it like that, of course, but in practice it doesn’t make much difference.

The right of older people to decide for themselves. What do I want then?

My ideal is that old people should be able to go to a doctor—either their general practitioner or a designated physician—to obtain the means by which, at the moment that it is right for them, they can put an end to their life in a way that is acceptable to themselves and to those around them.

That moment may be defined by the prospect of pain so severe that life is unbearable.

But it may also be that the elderly person recognises that the time has come when he can no longer take care of himself: a time when he will have to find a nursing home where he will become dependent for care on others and where he has to spend his last days among only old people.

It is, of course, good that such homes exist, and it is good that there are people who are content to become dependent on others.

But many old people who go to such homes to visit elderly relatives or friends find it almost terrifying to think that they, too, could end up there.

These people have only one thought: if only I could be spared that, and in this – “that” – is taken to mean, not only the bleakness of this institutionalised existence but also one’s loss of dignity.

Why then should such older people not be allowed to take matters into their own hands, to save themselves from becoming heavily burdensome on the community.

Why not allow them the peace of mind that comes from knowing that they are able to prevent such an existence: an existence which they feel is unacceptable to them.

To go before one’s time has come, at the moment that they want to?

It is impossible to predict how often such an opportunity, if offered, would actually be used.

It can hardly be doubted that the number of suicides by elderly people would increase.

But is that a reason to deny old people the possibility and peace of mind?

When one meets a reasonably happy sixty-year-old person and hears that he or she attempted suicide at the age of thirty, one will think to himself: it is good that their attempt failed.

But stop by a care home to visit an elderly relative or friend: you will find far too many old helpless people, silently staring into a corner or mumbling something unintelligible, often unable to eat by themselves, relying on caretakers for all their needs.

Who would not think “It’s a good thing none of these people had the opportunity to end their life earlier”?

What I am advocating here assumes greater autonomy for older people than has hitherto been considered in discussions about euthanasia.

Perhaps there is something to be said for restricting the option advocated here, at least to begin with, to the elderly living alone.

A suicide of a non-single person does affect greatly the life of the person with whom one lives.

On the other hand, in the case of a cohabitation, the danger of unacceptable pressure is perhaps greater.

But what seems important to me in any case is that the problem must be discussed separately from the euthanasia problem of the sick person.

Or am I overestimating the number of old people with the concerns these comments are about?

Author Huib Drion, ‘The right of older people to decide for themselves’

This letter has been edited from the Dutch and also for length.