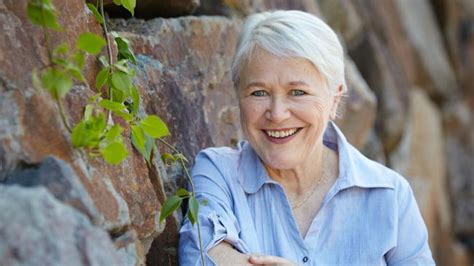

Annah Faulkner

Annah died in March 2022

Annah Faulkner died at home in Tasmania. An award-winning writer, her suicide note is poignant, thought-provoking, life-affirming and tragic.

Acclaimed Writer Annah Faulkner Leaves Literary Suicide Note

Annah Faulkner’s final non-fiction writing in the form of her suicide note is poignant, thought-provoking, life-affirming and tragic.

It tells of a plea for the rational elderly to be better understood and respected in their end-of-life decision making.

To read Annah Faulkner is to understand the work of Exit International …

An Open Letter to Australia, and the World

My husband’s slippers lie on the floor beside his chair.

But he has gone. He died last year.

Immediately, I wanted to follow. However, wanting to give God or fate a chance, it was a few months before I realised if I wanted death, I’d have to organise it myself.

My desire to die is not a dummy-spit.

I haven’t wilted, baulked at challenges or been reclusive.

I’ve spent exhaustive months wrestling with our finances which are healthy enough for a comfortable lifestyle.

I am past the shock of initial grief. I am sad but sadness hasn’t prevented me from accepting all invitations and being (after the first few months) good company, as well as enjoying those I’m with.

I read, do jigsaw puzzles and help my friends with their projects. I go for walks, smell roses (literally), and appreciate the splendour of our magnificent, though ransacked planet.

I am grateful for friends and for the life I’ve had.

But whatever meaning I derived from that life, including past work, interests and hobbies, disappeared with Alec.

The best analogy I can summon is it’s as if I’m sitting in an empty classroom, waiting for a teacher who has gone, and will never return.

My life is over, and for me, that is perfectly okay.

There is nothing left I want to do.

It’s been rich and full, with three careers, extensive travel and wonderful experiences.

I have given serious consideration to what life might be like if I chose to live on. I am not a group person but I have investigated various groups and all manner of voluntary work.

Palliative care, I feel, would be worthwhile but for various rules and reasons all I could get was housekeeping. No reading to, listening to or chatting with patients.

In planning to take my life, I have weighed five things:

Friends, conscience, circumstances, will and wish.

I’m nearly 73. I have no children or grandchildren, my only family is a brother whom I love but rarely see. I have beautiful friends, but not in quantity, and those I have are scattered across three states.

Most are older, and likely to die before me. Loneliness, already all-consuming, will bite even harder. Taking my own life will cause great distress to those who love me, and I truly and deeply regret that.

But I cannot live solely for purpose of protecting other’s feelings. My wishes, and my will, at a profoundly deep level, are for release.

But … How?

Sleeping tablets are not what they used to be. No overdosing with a bottle of Nembutal.

No fewer than 2,400 temazepam are needed to kill yourself, and even then, it’s not guaranteed. You might finish up a vegetable.

Despite suicide being legal in Australia, our authoritarian overlords will do everything possible to deny the questor a peaceful death, forcing him or her into a grubby and brutal exit.

Nembutal, the drug which has peacefully seen off thousands of animals, is forbidden to humans.

Exit International, the organisation to which I belong and am hugely grateful, has no legal or practical ability to offer Nembutal to its members.

Indeed, it warns that virtually all on-line sites offering the drug are scams, making it virtually impossible to obtain at all, let alone import (illegally) into Australia.

This forces people like me into desperate and desolate alternatives: hanging, poisoning, falling before a train, slitting my wrists, crashing my car, overdosing on heroin or methamphetamines, if I can get them.

Further, many of these gruesome options risk incomplete transition. In other words, a life of paraplegia, brain damage, psychiatric institutions where drugs aplenty will keep you nearly comatose but not let you die.

Society deems life sacrosanct (I’m not talking about abortion – that’s another conversation altogether), its right enshrined in locked-and-bolted law, but the right to death – the most inevitable part of life, is denied – both as a choice and, increasingly, as a natural process.

People flap and squawk in the face of suicide:

“Somebody should have done Something to stop it!” Why? What is the virtue of keeping me alive against my will? Life is not sacrosanct at the cost of joy.

What should be protested is people not being allowed to die in compassionate ways when they choose to do so.

Society, and religion – which generally reflects its society – deem suicide wrong; a thoughtfully-considered desire to die some kind of moral malignancy.

The grieving widow is a cliché. Legions of psychologists/psychiatrists/counsellors will diagnose grief-induced depression.

Yet I am not a cliche.

I am the only person in the world who truly understands me.

Not everyone who wants to die is mentally unhinged.

No individual or group has the spiritual or moral authority to dictate how and when people should die.

Suicide will continue, and ever-tightening laws will make it ever more bloody.

Nembutal, which puts you peacefully to sleep and you die, is Public Enemy No. 1. Why – when suicide is legal?

Glimpse my future:

Unavoidable physical and/or mental decline.

Pain, maybe dementia, loss of competence, incontinence, friends and independence disappearing.

My current living arrangements are not physically sustainable and I will finish up in either a small unit with in-home care, or a nursing home.

These prospects, for me, represent a living hell. I do not want to become an old lady forced to endure a life of ever-decreasing quality, in addition to clogging up an already clogged health system, and if that smacks of self-pity, I’m annoyed with my skills as a communicator.

A society that bans one of the few peaceful deaths available is neither compassionate nor liberal.

Australia, congratulating itself on being democratic and open, is starched rigid with laws.

Calm, constructive conversations around self-compassionate, elective deaths are ridiculously overdue, yet so many people reel back in horror. Why? Death is not the enemy. Fear and ignorance are our enemies.

Massive efforts go into keeping people alive, yet not a single, compassionate way allows them to die by choice.

A decision to die – mine, anyway – is not failure.

It is not a failure of friendship, vigilance, society or of me. I am not a pathology in want of treatment.

Any discomfort around my death belongs to others.

Most people want to live long lives, especially those with families. I completely understand and support this aspiration, but I ask in return that they recognise that for whatever reason, some people – sick or not – have had enough.

There are more of us than you might think. Armies of older people are appalled and terrified by their inability to choose when to die.

In advocating for the legalisation of Nembutal I’m not suggesting unobstructed access, instant hand-outs based on impulsive decisions. (Youth suicide is not the subject of this discussion, it’s an entirely different conversation.)

I speak for people who, like me, have lived long and well, have reflected deeply on their reasons for wanting to die, and understand the consequences of their decision, especially on those who love them.

My quest is for Access and Process.

Access to an elective, peaceful death, and processes which allow me to discuss my decision with the people I love.

At the moment, such is the current general (unhealthy) abhorrence of death, someone would try to stop me, and if they didn’t, they could be charged with aiding me.

My husband was my best mate, intelligent, philosophical, engaging and vibrant, my greatest love and champion.

But what really set him apart was his capacity for forgiveness and an absolute unwillingness to judge.

If not for my friends at Exit International I would be unspeakably lonely.

Ironically, I have never met a more vibrant, funny, intelligent, alive group of people in my life.

Many, if not most, simply want the certainty of being able to die if and when they choose. Most will not choose, yet that option makes life feel more precious to them.

As much as it is possible to understand anyone else, they understand me. They do not judge. They neither encourage nor discourage me.

They hold me in their love. But if they dare hold my hand while I die, they will be charged with assisting in my death.

A compassionate society does not deny its citizens the right to choose.

Please, dismantle Australia’s sanctimonious, outdated and cruel laws and make this society a wise and kind one.

Let me die in peace.

Legalise Nembutal.

Annah Faulkner

8th March, 2022

Back to Exit stories