June 29, 2025

Exit Member Author Maurice Gee Calls Law Cruel & Intrusive

Exit Member Author Maurice Gee Calls Law Cruel & Intrusivereports Virginia Fallon in The Press.

Acclaimed author Maurice Gee’s death has put assisted dying back in the spotlight – with some Kiwis pushing for change, and others fearing undue pressure on the elderly and disabled.

In the end, Maurice Gee was right where he wanted to be.

He felt good in that little house on the corner of Nelson’s King and Nile streets, surrounded by a ficus hedge that gave him all the privacy he needed.

He’d lived a good life: a wife Margareta – although she was now in a dementia unit; three children – Nigel, Emily and Abigail; and grandchildren Nicholas, Lewis, August and Florence.

At the age of 93, Gee had enjoyed decades of being loved by family, adored by friends, and respected as one of the greatest New Zealand writers of the 20th century.

Yet on an overcast Thursday afternoon, he died alone.

Gee’s last note detailed a carefully considered choice, made without influence, and a death faced “calmly and cheerfully”.

But he would have rather not been alone when he died, wrote the long-time supporter of voluntary euthanasia.

“I wish my children could be with me at the end, however a cruel and intrusive law prevents this.”

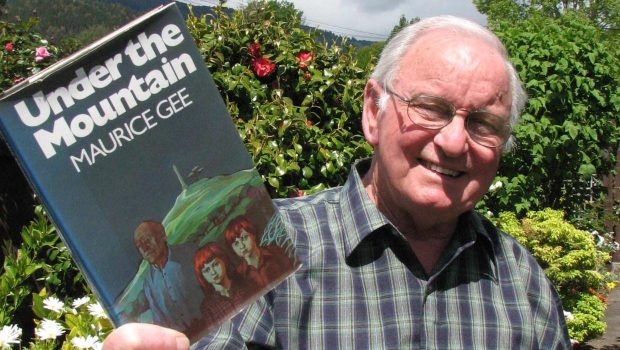

Pioneering Exit Member Maurice Gee shortly before his recent death. Maurice’s Exit Membership number was 1688. He was one of the originals!

While Gee’s death is widely mourned by those who loved and admired him, it has also reignited public debate over that very law he slammed in his last writing.

Currently, New Zealand’s voluntary euthanasia framework gives people with a terminal illness that is likely to end their life within six months, the option of requesting assisted dying.

But that may well be up for change, with a parliamentary member’s bill proposing an expansion of the criteria for folks with incurable conditions. And just as that’s bringing hope to many, others fear that elderly and disabled people will be coerced into a choice that isn’t really a choice at all.

Since the revised legislation was passed as the End of Life Act in 2021, after a referendum that saw 65% vote in favour, 2975 Kiwis have applied for the right to die as of March.

Of those, 1213 have been successful, including Tracy Hickman, a 57-year-old with cancer, who chose to end her life on a secluded beach, the sound of surf in her ears, surrounded by the people she loved.

“I can’t think of a better way to go,” she told the Sunday Star-Times two weeks before her death in May last year.

Also Dr David Hadorn, a 72-year-old with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy, who worried about people being denied the option he was given.

“It is stupid and inhumane and cruel,” Hadorn told The Press of the eligibility criteria, speaking days before his death in February.

“Doctors can’t tell how long you are going to live, and it is totally irrelevant anyway. The fact that a person is suffering right now is all you need [to know].

Hadron felt lucky to be dying fast enough to qualify for an assisted death, saying nature could be cruel as any guard in Iraq.

“I would do it today if I could,” he said two days before he did.

And then there are the folks who would like to die like this but can’t.

Frank Sanft, a 99-year-old World War II veteran, has been begging to die for three years now, yet this year he’s been denied twice.

“It’s a miserable life,” he told the Star-Times in 2022, speaking of his suffering: the constant pain, the osteoporosis that breaks his bones, and the heart problem denying him anything stronger than paracetamol.

Sanft isn’t up to an interview these days, but his daughter Karen Holder says things are even more miserable now.

“He’s basically bed-bound, he can shuffle to a chair… He lives in a small room and that’s it.

“His quality of life, the last three years, you wouldn’t put your dog through it.“

Holder is keen to make clear she’s not so much advocating for her father’s right to die as supporting his desire to do so.

“He’s been so disappointed each time he’s been denied. He says if he had known what he does now – what he would have to go through – he would have got on a plane and gone to Switzerland.

“What Dad’s got isn’t terminal. He can go on and on; it’s just terrible.”

Ann David, president of the End-of-Life Choice Society, says Sanft emailed “every single member of Parliament” for help with his plight.

She knows that because he asked her to both help him – “that poor man working on an iPad with the technological powers of a nearly 100-year-old person” – and make sure she also received the responses.

“So I know how people replied: ‘Sorry no can do, we need a change in law’.”

David knows that too; she’s heard from many desperate people who have wanted assisted dying but don’t meet that six-month criteria.

“They just suffer until they do die the very kind of death that they were trying to avoid.”

Others, like Gee, have taken matters into their own hands, dying alone because anyone with them could face criminal charges for aiding and abetting a suicide.

“That’s why he would have wanted them not there, to protect them.”

Ultimately, David says that those who don’t meet the criteria are left with very limited and uncertain options.

“You can voluntarily stop eating and drinking [VSED], which is as grim as all get-out; you attempt to end your life somehow…. Or you take the Swiss option.”

As for the former, Aubrey Welsh has both rare and first-hand experience.

Maurice Gee

Last year, when the Aucklander told the Star-Times that he planned to end his life though VSED, he also acknowledged his case was an unusual one.

He wasn’t in pain, or suffering from a terminal illness, and certainly not depressed. What he was though, he said at the time, was ready, having lived “a completed life”.

The 69-year-old travelled the world, settled his affairs, then hunkered down at home to starve himself to death: except four weeks in he’d consumed too much water, was still very much alive, and was persuaded – or “peer-pressured”, he says – to change his mind.

This week, Welsh says it was one heck of a learning experience, both about the body’s will to live and society’s view of death. He’s had cancer since, and while now free of it, he’s not ruling out making another choice next year.

“We make thousands of decisions in our lifetimes and I do not understand why we can’t make one of the most important ones – the last one.”

Libertarian free choice, of course, is what ACT professes to be all about, so it’s no surprise the party is advocating for more of it.

Leader David Seymour, who successfully championed the assisted dying laws through Parliament, is furious that a war veteran like Sanft is being forced to live such a miserable life.

“Frank is literally a hero given his military service, and he is a perfect example of why we should never have had that six-month requirement.

“When I first started talking to Frank I thought there was a window while there was a very large liberal Labour majority, and I really regret I never got a bill up before the election.”

Seymour’s first bill allowed a person who had a grievous and irremediable medical condition to seek assistance, but that had to be watered down to gain support from the Green Party which, unlike Labour and National, was voting as a block on the conscience issue.

Any future amendment is likely to rely on the Greens as well, says Seymour.

“Yet I know that the change will inevitably happen because the compromise I had to make back in 2019 is ultimately illogical.”

As for the Greens? This week, their health spokesperson Hūhana Lyndon said the party’s health policy states it would “regularly review the process and criteria for medically assisted dying to ensure it is patient-centric and accessible”.

“However, we will also protect the autonomy of people, including disabled people and elders, against coercion during end-of-life decision-making.

“Should the bill be pulled, we would need to have a wider discussion with the party about our stance, therefore we wouldn’t look to confirm our support at this stage.”

ACT’s Todd Stephenson is the man behind the bill and says it will expand eligibility while still “retaining all other safeguards”.

Currently, it’s being redrafted to pick up all the recommendations made in a recent review, ones that Stephenson says were both sensible and mainly about clarity.

But it would remove that six-month criteria.

“Someone might be living with degenerative illness which is going to end their life, no doubt about it, but we can’t say it’s going to happen in six months.

“Then you have the next one – the irreversible physical decline or capacity, when your suffering and pain can’t be relieved in a manner which is tolerable, and you’re competent of making a decision.”

All of those things will have to be met, he says, while assuring that advanced age, mental illness or disability aren’t included.

“It is a choice. No one is forced to do this. You can change your mind at any time; you can go through the process, be approved, and still say you don’t want to do this.

“It’s providing people with a choice to die with dignity when they do have a terminal illness.”

Yet for some New Zealanders, the matter of choice is the very issue at play.

Dr Huhana Hickey, a lawyer and disability advocate who has multiple sclerosis, opposed the End of Life Act, not because she doesn’t believe in autonomy or free will, but for worries about its effect on the disabled community.

The backlash backed that up, she says of the death threats and vitriol that followed her stance.

“During the campaign, last time, we were threatened and told to die. We were told we were using up resources and wasting money in the health system.

“There’s a lot of eugenicists in this country, and you become less valued. This is happening because people now think that euthanasia is the answer for everyone.”

Disabled and elderly people are already maligned and considered to be suffering by much of society, Hickey says, and expanding the criteria for assisted dying will only feed into that.

“[It’s] bad enough when everyone else thinks you’re a burden, worse when you’re forced to believe that too.”

Hickey would like to see the natural conclusion of death discussed openly and honestly, folks empowered by knowledge, emboldened by assurances that it can be painless, and gentle, and not lonely.

“Before they extend the law, how about making an equal option so that it’s a true choice?

“The only way that’s going to happen is if we have hospice and palliative care fully funded and able to meet the alternative.”

But Maryanne Spurdle says that neither is either. The research manager for the Maxim Institute recently authored a report finding that when it comes to euthanasia, choice is swayed by, well, a lack of it.

“We cannot accept choice on face value if it skews one way or another.”

Spurdle says that just as the current law requires a six-month terminal diagnosis, access to palliative care in NZ is “incredibly patchy”.

“That means people can be approved for euthanasia even though their suffering is largely due to isolation or poor symptom management or even fear of the unknown.

“The system doesn’t check those basic needs are met before letting them end their life.”

And if palliative care was universally accessible, she says, we wouldn’t have to wonder how many people were opting for euthanasia to end suffering that has actual solutions.

“Many Kiwis can’t access good end-of-life care, and for them, the ‘choices’ they’re left with read more like a game of ‘Would you rather …?’”

That ‘would you rather’ might mean choosing between dying in a hospital corridor or at home snuggled under your duvet.

True choice, says Spurdle, is about real options. She’s worried that when a terminal diagnosis means ‘You could opt for euthanasia’, we’ll default to ‘You should consider euthanasia’.

“For terminally ill Kiwis who don’t have good access to palliative care – -most of whom are rural, Māori or Pacifika – it absolutely is easier to get assisted suicide than assistance to die well.

“Euthanasia is fully funded. Health New Zealand will send a physician to any corner of the country. Many of those corners have no hospices and no palliative care specialists.

“We – and especially doctors – ought to start conversations by finding out what people need in order to live well in the time they’ve got.

“Defaulting to euthanasia communicates hopelessness.”

But for those who seek it, it can also communicate love.

Exit Member Author Maurice Gee Calls Law Cruel & Intrusive

Maurice Gee, who wrote so very many good words in his life, wrote another few hundred at the end.

“I am cheerful and not acting out of depression but I am 93 and very unsteady on my feet and have had several falls lately,” he explained in his farewell note.

“Also, my mind is slowing down and I am getting seriously forgetful, and this causes all sorts of problems.”

He wrote that he was in good command of his faculties but feared “the threat of senility and loss of command of both body and mind.”

And then there was the wish that his children could be with him, and that “cruel and intrusive law” preventing it.

“I love them very much,” he wrote of those children.

He ended with a private joke to them, a misspelled word with a meaning that’s none of anyone else’s business.

But his children shared all the words with the Star-Times, and the last ones belong to his daughter.

On Wednesday, Abi Gee wrote in an email that she’d been speaking to Ann David about the proposed amendments Todd Stephenson is working on.

“After the phone call I suddenly thought – if Dad knew he could be part of changing something like that he would consider it his greatest achievement.

“It would be far more important to him than receiving an award, prize or critical acclaim, or having a movie made out of one of his books, because it would help so many people in such a deeply meaningful way.

“He wasn’t religious but he was a humanist and a very kind and gentle person.

“So that’s why we’re sharing all this with you, it’s a way of honouring him.”

Exit Member Author Maurice Gee Calls Law Cruel & Intrusive