July 30, 2023

Dr Death and his search for the best way to die

De Volkskrant, by Maud Effting & Haro Kraak

Dr. Death and his search for the best way to die writes Maud Effting and Haro Kraak in de Volkskrant, NL

As founder of Exit International, Philip Nitschke fights for access to information about a soft, self- chosen death. “I think every adult with common sense is entitled to that.”

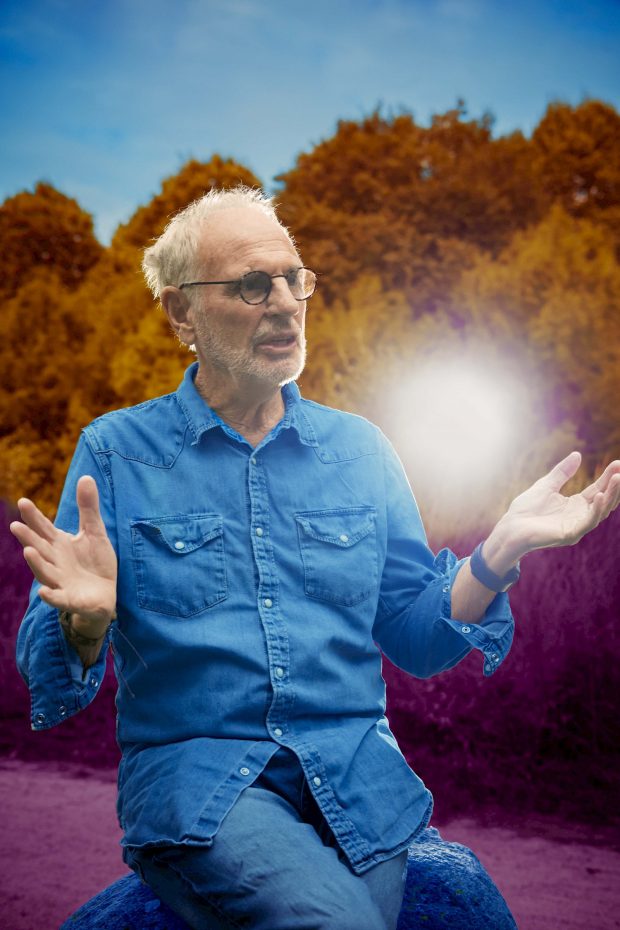

On his idyllic houseboat near Haarlem, Australian Philip Nitschke (75) sits on the couch in his very old jeans with rips on both knees. He is a doctor and a physicist with a PhD, specializing in laser physics. But actually he has been working on a completely different subject for years: the soft, self-chosen death.

He has just told about his latest invention: the Sarcopod, a futuristic capsule in which people with a death wish can lie down and press a button. The capsule is then filled with nitrogen gas and a painless death follows within five to ten minutes. At least, that’s the idea.

“Soon I’ll lie in it and turn it on,” says Nitschke, “to feel if that gas isn’t too cold.”

“I’m not crazy about this idea,” says his wife Fiona Stewart, who serves coffee and cake.

“I’ll bring an oxygen mask,” says Nitschke.

Stewart: ‘When I first met him, he once put a plastic bag over his head to test how quickly the oxygen level went down. It freaked me out .’

Nitschke grins. “We have a huge waiting list for the Sarco,” he says.

In the coming hours, Nitschke will tirelessly explain why he fights for the people who call, email and text him almost every day.

“Everyone only wants to know one thing,” he says. “What should I take to make sure I die, and where can I get it?”

Nitschke is the founder of Exit International, the organization that advocates for the right of people to end their lives independently and peacefully. In 2006, he caused an international stir with a book detailing dozens of suicide methods: The Peaceful Pill Handbook.

In the book, which the organization now mainly sells as an e-book, he explains everything for hundreds of pages with the help of photos and videos: from the illegal pentobarbital to Drug X.

And not only that. It also lists where all resources can be obtained – information that can have major consequences.

His actions are so controversial that he is nicknamed Dr. Death got. The Australian doctors’ federation also called him “a serious risk to public health” and threatened to remove him from his profession. In protest, he himself burned his doctor’s certificate.

After several suicides of members, the police raided Exit International premises, confiscated telephones and computers and interrogated Nitschke for hours. In 2016 he felt so limited in Australia that he emigrated to the Netherlands, where he believes people have the most progressive ideas about euthanasia.

•

Do you feel rushed?

Nitschke: ‘Not really.’

Stewart: ‘I do feel stressed. A fatwa was issued against him on Twitter.’

Nitschke: ‘Let’s not exaggerate. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t get a huge amount of emails thanking me for my work. But there are also people who are angry because they hold me responsible for the death of their children. And we once had the police at the door after a death threat. When I saw how seriously the police took this, I panicked for a while.’

Do the parents of those deceased children have a point? Are you responsible?

“There’s no easy answer to that. We understand the sadness and anger and we sympathize with them. Still, we don’t think it’s a good reason to stop our book. We are an easy target for grieving parents.

Their anger stems partly from guilt. Parents often feel that they could have prevented their child’s suicide.’

Have you ever provided lethal drugs yourself?

Nitschke: ‘No. I can not do that. I can make sure someone knows how to get it. But in the end, people have to do this themselves. You can’t expect other people to kill you for a while.’

Why not?

It’s their decision, not mine. Choose an injection or a drink for euthanasia in the Netherlands. More and more people are opting for the injection. I think they like the doctor doing it. As if he approves, as if death is a shared responsibility. I’m in favor of that drink.’

Are you ever tempted to help in distressing cases?

‘We don’t do it, but it sometimes happens in the network. During a workshop in London, a participant stood up and asked: Does anyone have any leftover suicide powder?

Another visitor shouted: yes, I have a kilo at home. I intervened: we are not going to talk about this now, but if you want to have a cup of tea outside, go ahead.

We are extremely careful, but many people have no idea what the legal consequences are. They just think: oh yes, I’m here now, why not?’

•

Nitschke’s struggle can be summarized as an endless hunt for the ‘best’ remedy.

The fact that so many peoplewant his help has to do with legislation: euthanasia is only legal in eight countries worldwide.

In addition to the Netherlands, including in Belgium, Canada and Spain.

In most countries, euthanasia is only permitted in cases of unbearable and hopeless physical suffering. Many people are therefore not eligible for existing schemes.

For example, in Western countries there is a growing group of elderly people who want to be able to determine for themselves when their life is complete and who want to have access to a substance that causes a peaceful death. In the Netherlands this is called ‘Drion’s pill’. But such a pill is not just available.

‘There is really only one drug that is the very best,’ says Nitschke, ‘and that is pentobarbital. It’s the best thing in the world: all the people I’ve seen take it fell asleep within a few minutes. But the problem is, it’s almost impossible to get. That makes it pretty useless.’

Pentobarbital is used in capital punishment in some countries and is on an international list of banned substances. ‘You will only find it if you get on a plane to Peru or Bolivia yourself. It is no longer available on the internet.

Yes, if you type in Nembutal (the brand name of pentobarbital, ed. ), you get millions of sites.

All scams. There are even sites that misuse our name or put my photos there, and then deliver nothing.’

Until recently, there was only one reliable internet seller of Nembutal in the book, he says. “He was in Mexico. But he’s gone. Traceless. We don’t know where he went.’

A hunt for alternatives has now started. For example, the demand for suicide powders Middel X and Middel Y, both legally available preservatives, has increased in recent years. “The desire to have something in the bedside table is enormous.” But that trade is also restricted.

This month, the Dutch judge sentenced Alex S. to two years in prison for selling Drug X, after which at least ten people died.

“A very cruel verdict,” says Nitschke. “The judge paid disproportionate attention to how horribly these people had died, while they chose it themselves. Why so many people are interested in what Alex S. has to offer, he didn’t try to understand.

The lawsuit was mainly intended as a deterrent: don’t buy this stuff.’

Are you concerned about the direction of the debate in the Netherlands?

“Certainly, but not only because of this verdict. The discussion about a Completed Life Act (dying aid for the elderly who feel that their life is complete, ed. ) has been at a standstill for years. Very disappointing. Politicians prefer to avoid this huge problem because it is so complicated.’

It is 1996 when self-chosen death enters Nitschke’s life for the first time.

As a doctor, he performs the world’s first legal euthanasia in that year, after a law has been passed in one state in Australia that makes this possible. His patient is a seriously ill man with prostate cancer.

Even then, Nitschke is already convinced that not he, but the patient should take the last step: he assembles a device that he calls the Deliverance Machine . With a few clicks on a laptop, the patient can initiate the process himself.

” Let’s do it ,” the man says to him that day. Sweating, Nitschke walks to the corner of the room and waits to see if his machine will work. “I knew he wasn’t perfect,” he says. But after half a minute he sees the deadly liquid entering the veins. Nitschke is relieved. The man dies in his wife’s arms.

“It changed my life,” says Nitschke.

He later writes in his autobiography that this was never his plan: he fell into it because he felt responsible for desperate patients. Nitschke is lonely at that time, he writes.

At the time, he was the only doctor in Australia who dared to do this. While he has heated conversations with people who want to die, a fierce debate arises about the euthanasia law. He helps three more patients die, until parliament repeals the law the following year.

But then something started to burn in Nitschke. He starts giving workshops on suicide. Nearly a decade later, he writes The Peaceful Pill Handbook .

“It was Fiona’s idea,” says Nitschke. Stewart, his wife, is a journalist, lawyer and sociologist. He met her in 2003 at one of his workshops. Stewart: “I saw him tell the same thing three times a week.

And then I thought: why don’t you write this down?’ The book is initially given a Restricted 18-plus rating in Australia, comparable to the sale of porn, but after a few months it is still banned. Nitschke: ‘The only book with which this has happened in the past fifty years.’

Then they focus on foreign countries. In New Zealand the book is censored: large parts are painted black. They decide to move to the US. Nitschke: ‘Because there was no publisher who dared to do it, we published it ourselves. And two years later we went online. Then we didn’t need anyone anymore.’

Initially, you only gave information to terminally ill people. Then you publish a book that is freely accessible. What has stretched your boundaries?

Nitschke: ‘My view of death has been changed forever by Lisette, a 77-year-old French professor. After a workshop, she told me that she wanted to be dead in four years, before she turned eighty. She wasn’t depressed, but she was fed up. She had collected pills and wanted to know if the dose was high enough.

I brushed her off, but she kept coming back. One day I shouted: man, you’re not even sick, go on a cruise or something. Then she lashed out at me hard. She said, ‘Mind your own business, doctor.

This has nothing to do with you. You walk around here deciding who gets your information, and who doesn’t, but what gives you that right? Who do you think you are?”

How did you react?

‘I flinched. Because I knew she was right.’

In the end, he tells her that she has enough drugs to die as many as four times. Lisette dies in 2002 of an overdose, two weeks before her eightieth birthday. In her farewell letter, she thanks him and states that she had a good life. A documentary is being released about her death and his role in it, which causes a lot of commotion.

What did this change for you?

“After that I decided I don’t want to know why people want to die. I do not give a hoot. I’ve talked to people who had stupid reasons. But if you want to die, you are in your right mind and you want to do it yourself, then it is not for me to judge whether you have a stupid reason for that. It’s your reason.’

Yet Nitschke does not give his information to just anyone. The minimum age for purchasers of The Peaceful Pill book is 50 years old. Those who pay $ 95 get access to the digital edition for a year, but must identify themselves by means of a video and are screened. Stewart: ‘We have six freelancers worldwide who check the identity of all buyers as detectives.’

•

How far do you go in that?

Stewart: Very. We refuse a substantial part of the requests.’

How many books do you sell?

Stewart: ‘Somewhere between 5 and 30 a day. Sometimes sales suddenly skyrocket.’

Nitschke: ‘Then we try to find out what’s going on.’

Stewart: ‘In 2015 , The New York Times published a piece about a well-known professor. She bought pentobarbital from our book through an address in Mexico and took her own life. She had Alzheimer’s.

We didn’t know what we were experiencing, there was suddenly so much demand for the book. Oh my god, I told Philip, we can’t handle this at all.’

Yet the information can reach very young, vulnerable people who can commit suicide on a whim. Isn’t that a reason not to publish?

Nitschke: ‘We are doing our best, but it is not watertight. The information always leaks out. And thousands of elderly people around the world are desperate for this information and are very grateful to us for it.

Are they then not allowed to have access to this at all because there is a small group of teenagers who commit suicide on a whim? I think you have to weigh the peace of mind of the elderly against the tragic suffering of the teenagers and their parents.’

How do you weigh the two against each other?

‘It’s very difficult, I don’t know exactly. We are getting more and more criticism about this, especially from the US, because the use of Substance Y has risen sharply there. That would be our fault, because we were the first to publish the information about it.’

Isn’t this also a revenue model for you?

We often get that accusation. That we get rich from the suffering of teenagers. But it’s not right. Look at what we do with the money. We have now invested a million euros in the development of the Sarco. That money comes from sympathizers and from the proceeds from the book.’

They talk about the battle they are fighting with so-called suicide chat rooms , where teenagers exchange information about suicide and sometimes even encourage each other. Nitschke, indignantly:

‘Every update of the book is posted on those forums almost immediately. People just take hundreds of screenshots of all pages. We’ve managed to take illegal copies offline a few times, but it’s an awful lot of work.’

Stewart: ‘As soon as we catch people, we stop their digital subscription. Sometimes these are just seventies, huh. It’s unbelievable, but some people are so radically liberal that they think this should be available to everyone .

They don’t care that young people see this too. I totally disagree. I think we should protect 18- year-olds from themselves.’

She looks at Nitschke. “But I’m more worried about this than he is,” she says.

Are you for radical openness?

Nitschke: ‘My vision is simple. Don’t keep people in the dark . In many countries, governments try to reduce suicide rates by keeping information and lethal drugs away from people.

The thinking is, if people don’t know how to commit suicide, they won’t do it. I find that a strange approach. In a healthy society, people receive good information, so that they make rational decisions.

Look, we also give 18-year-olds guns and send them into wars. I believe that every sane adult has the right to this information. But…’

Stewart: “He means this philosophically.”

Nitschke: ‘… But the political reality is that you can’t get away with that. That’s why we set that age limit of 50 a long time ago. They must be adults, with life experience – whatever that may be . It was Fiona’s idea.’

Stewart: “I always tell him what he can’t do. In some ways he is his own worst enemy.’

Are you a libertarian?

Nitschke: ‘Yes, that is probably the best description. I realize that there must be conditions for obtaining these kinds of resources, but my underlying belief is that everyone should be able to do what they want, as long as it doesn’t harm others.’

Stewart: ‘But what kind of society would we live in if it were every man for himself? That sounds like Trump country.”

Nitschke: ‘Let’s not go on about this. Then we’ll get into another huge fight.’

Stewart: ‘He has a long history of political action: against the Vietnam War, against nuclear weapons, for Aboriginal rights. As a teenager he was probably unbearable.’ She laughs. “Have you told them about your citizen’s arrest yet?”

Nitschke says he once pointed a gun at a man’s head when he was seventeen. ‘My car radio was stolen, but the police said: come on kid, who cares ? But I wanted my radio back. I installed a new one, opened the car window and sat in the back. I waited three nights. When they finally put their hand in that car, I jumped out.”

With your gun?

‘A Browning automatic, 22 millimeters. I’m from Australia, I had guns in those days. I shouted: hands up . One ran away, the other stopped and said don’t kill me . Finally, I delivered him to the police. It was in the newspaper the next day.’

What does this say about you?

‘That I want to solve things myself.’

•

Have friends or family ever asked you to help them die?

‘My mother. That was a very frustrating situation. She was 96. One day my mother had said to a nurse at the nursing home: I feel terrible, I wish I were dead. On my next visit the nurse said to me: your mother is depressed and says she wants to die, we are worried about your visits.’

Because of your reputation?

“Yes, they thought I talked her into wanting to die and that I would give her the means. I felt so stupid that I hadn’t arranged anything. I should have been smarter. Faster. Then she wouldn’t have had to waste years against her will in a bloody nursing home.

Although she probably never took the drugs, because the risk would be too great for me. That’s how she was. Eventually, after a few years, she contracted pneumonia and died. But it should never have happened this way.’

Did you feel guilty?

‘Yes. I feel terrible about this,” he says with difficulty. “It still wakes me up sometimes.”

And then he is silent. Nitschke, who talked a lot throughout the interview, doesn’t know what to say for a

moment.

Did your mother’s death change anything in your thinking?

Since I made this mistake, I urge people even more: get the resources in house. Do it yourself, put them away for later, I say to them, don’t wait for your son or daughter to do it for you.’

CV PHILIP NITSCHKE

Born in Australia in 1947

1972 PhD in laser physics

1989 graduates as a doctor

1996 Performs first legal euthanasia in the world

1997 Founder Exit International

2006 publishes The Peaceful Pill Handbook

2015 burns his doctor’s certificate

2016 emigrates to the Netherlands

2017 Sarco Pod concept model launch

ABOUT THE CREATORS

Maud Effting is an investigative journalist for de Volkskrant and has written about transgressive behavior at De Wereld Draait Door and NOS Sport, among other things. She also follows all developments surrounding voluntary end of life, euthanasia, suicide and Substance X. She won the journalistic prize De Tegel for her work and was nominated for Journalist of the Year in 2017.

Haro Kraak is a reporter for de Volkskrant. He writes about cultural and social topics such as identity, gender, polarization, extremism and the end of life.

Sanja Marušić (31) is a Dutch-Croatian artist who explores the boundaries between photography and painting. She always adds color afterwards – digitally or with paint – so that her photos lie between fantasy and reality.