January 25, 2026

AI, Sarco & the Right to Die

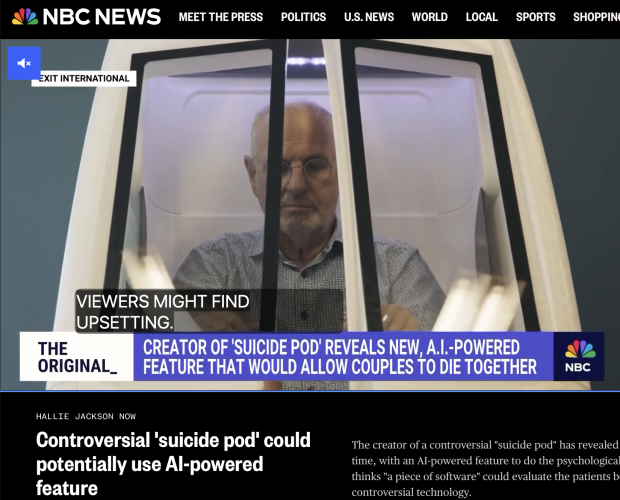

The inventor of the controversial Sarco suicide pod says AI software could one day replace psychiatrists in assessing mental capacity for those seeking assisted dying.

Philip Nitschke has spent more than three decades arguing that the right to die should belong to people, not doctors.

Now, the Australian euthanasia campaigner behind the controversial Sarco pod – a 3D-printed capsule designed to allow a person to end their own life using nitrogen gas – says he believes artificial intelligence should replace psychiatrists in deciding who has the “mental capacity” to end their life.

“We don’t think doctors should be running around giving you permission or not to die,” Nitschke told Euronews Next. “It should be your decision if you’re of sound mind.”

The proposal has reignited debate about assisted dying and whether AI should ever be trusted with decisions as significant as life and death.

‘Suicide is a human right’

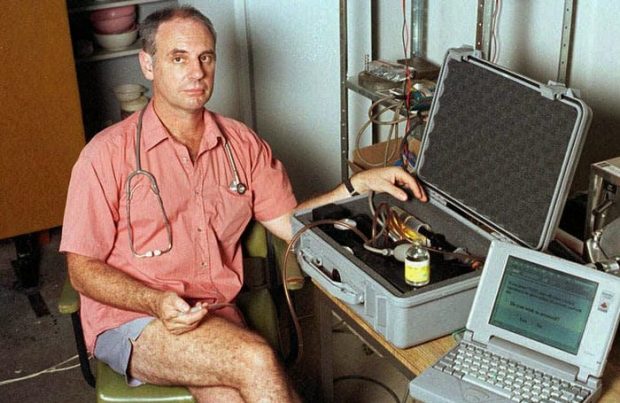

Nitschke, a physician and the founder of the euthanasia non-profit Exit International, first became involved in assisted dying in the mid-1990s, when Australia’s Northern Territory briefly legalised voluntary euthanasia for terminally ill patients.

“I got involved 30-odd years ago when the world’s first law came in,” he said. “I thought it was a good idea.”

He made history in 1996 as the first doctor to legally administer a voluntary lethal injection, using a self-built machine that enabled Bob Dent, a man dying of prostate cancer, to activate the drugs by pressing a button on a laptop beside his bed.

Philip Nitschke, founder and director of the pro-euthanasia group Exit International, attends a press conference in Basel, Switzerland, on 9 May 2018.

However, the law was short-lived and was repealed amid opposition from medical bodies and religious groups. The backlash, Nitschke says, was formative for him.

“It did occur to me that if I was sick – or for that matter, even if I wasn’t sick – I should be the one who controls the time and manner of my death,” he says. “I couldn’t see why that should be restricted, and certainly why it should be illegal to receive assistance, given that suicide itself is not a crime.”

Over time, his position hardened. What began as support for physician-assisted dying evolved into a broader belief that “the end of one’s life by oneself is a human right,” regardless of illness or medical oversight.

From plastic bags to pods

The Sarco pod, named after the sarcophagus, grew out of Nitschke’s work with people seeking to die in jurisdictions where assisted dying is illegal. Many, he says, were already using nitrogen gas – often with a plastic bag – to asphyxiate themselves.

“That works very effectively,” he said. “But people don’t like it. They don’t like the idea of a plastic bag. Many would say, ‘I don’t want to die looking like that.’”

The Sarco pod was designed as a more dignified alternative: a 3D-printed capsule, shaped like a small futuristic vehicle, which floods with nitrogen when the user presses a button.

Its spaceship-like appearance was an intentional design choice. “Let’s make it look like a vehicle,” he recalls telling the designer. “Like you’re going somewhere. You’re leaving this planet, or whatever.”

The decision to make Sarco 3D-printable, costing a reported $15,000 (€12,800) to manufacture, was also strategic. “If I actually give you something material, that’s assisting suicide,” he said. “But I can give away the program. That’s information.”

Legal trouble in Switzerland

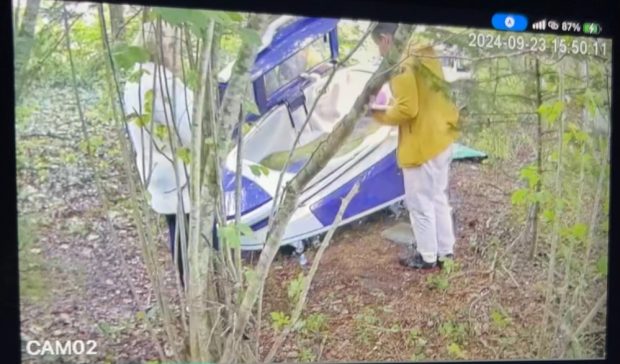

Sarco’s first and only use in Switzerland in September 2024 triggered an international outcry. Police arrested several people, including Florian Willet, CEO of the assisted dying organisation The Last Resort, and opened criminal proceedings for aiding and abetting suicide. Swiss authorities later said the pod was incompatible with Swiss law.

Willet was released from custody in December. Soon after, in May 2025, he died by assisted suicide in Germany.

Swiss prosecutors have yet to determine whether charges will be laid over the Sarco case. The original device remains seized, though Nitschke says a new version – including a so-called “Double Dutch” pod designed for two people to die together – is already being built.

Drs Florian Willet & Philip Nitschke, Sarco Press Conference, July 2024

An AI assessment of mental capacity

Adding to the controversy is Nitschke’s vision of incorporating artificial intelligence into the device.

Under assisted dying laws worldwide, a person must be judged to have mental capacity – a determination typically made by psychiatrists. Nitschke believes that the process is deeply inconsistent.

“I’ve seen plenty of cases where the same patient, seeing three different psychiatrists, gets four different answers,” he said. “There is a real question about what this assessment of this nebulous quality actually is.”

His proposed alternative is an AI system which uses a conversational avatar to evaluate capacity. “You sit there and talk about the issues that the avatar wants to talk to you about,” he said. “And the avatar will then decide whether or not it thinks you’ve got capacity.”

If the AI determines you are of sound mind, the suicide pod will be activated, giving you a 24-hour window to decide whether to proceed with the process. If that window expires, the AI test must begin again.

Early versions of the software are already functioning, Nitschke says, though they have not been independently validated. For now, he hopes to run the AI assessments alongside psychiatric reviews

“Whether it’s as good as a psychiatrist, whether it’s got any biases built into it – we know AI assessments have involved bias,” he says. “We can do what we can to eliminate that.”

Can AI be trusted?

Psychiatrists remain sceptical. “I don’t think I found a single one who thought it was a good idea,” he added.

Critics warn that these systems risk interpreting emotional distress as informed consent, and raise concerns about how transparent, accountable or ethical it is to hand life-and-death decisions to an algorithm.

“This clearly ignores the fact that technology itself is never neutral: It is developed, tested, deployed, and used by human beings, and in the case of so-called Artificial Intelligence systems, typically relies on data of the past,” said Angela Müller, policy and advocacy lead at Algorithmwatch, a non-profit organisation that researches the impact of automation technologies.

“Relying on them, I fear, would rather undermine than enhance our autonomy, since the way they reach their decisions will not only be a black box to us but may also cement existing inequalities and biases,” she told Euronews in 2021.

These concerns are heightened by a growing number of high-profile cases involving AI chatbots and vulnerable users.

For example, last year, the parents of 16-year-old Adam Raine filed a lawsuit against OpenAI following their son’s death by suicide, alleging that he had spent months confiding in ChatGPT.

According to the claim, the chatbot failed to intervene when he discussed self-harm, did not encourage him to seek help, and at times provided information related to suicide methods – even offering to help draft a suicide note.

But Nitschke believes that in this context, AI could offer something closer to neutrality than a human psychiatrist. “Psychiatrists bring their own preconceived ideas,” he said.

“They convey that pretty well through their assessment of capacity.”

“If you’re an adult, and you’ve got mental capacity, and you want to die, I would argue you’ve got every right to have the means for a peaceful and reliable elective death,” he said.

Whether regulators will ever accept such a system remains unclear.

Even in Switzerland, one of the world’s most permissive jurisdictions, authorities have pushed back hard against Sarco.

There have been many high-profile stories in which chatbots have effectively encouraged and enabled people experiencing mental health crises to kill themselves, which has resulted in several wrongful death lawsuits against the companies responsible for the AI models behind the bots.

Now we’ve got the inverse: if you want to use your right to die, you have to convince an AI that you are mentally capable of making such a decision.

According to Futurism, the creator of a controversial assisted-suicide device known as the Sarco has introduced a psychiatric test administered by AI to determine if a person is of sound enough mind to decide to end their life.

If they are deemed of sound mind by the AI, the suicide pod will be powered on, and they will have up to 24 hours to decide to move forward to their final destination. If they miss the window, they’ll have to start over.

The Sarco that is central to this whole thing has already stirred up quite a bit of controversy before introducing the AI mental fitness test.

Named after the sarcophagus by inventor Philip Nitschke, the Sarco was built in 2019 and used for the first time in 2024 when a 64-year-old American woman who had been suffering from complications associated with a severely compromised immune system, underwent the process of self-administered euthanasia in Switzerland, where assisted suicide is technically legal.

Sarco in the Schaffhausen forest, September 2024

She reportedly underwent a traditional psychiatric evaluation conducted by a Dutch psychiatrist before she pressed a button that released nitrogen within the capsule and ended her life because the AI assessment wasn’t ready at the time.

However, the use of the Sarco resulted in the arrest of Dr. Florian Willet, a pro-assisted suicide advocate who was present for the woman’s death. Swiss law enforcement arrested the doctor on the grounds of aiding and abetting a suicide.

Under the country’s laws, assisted suicide is allowed as long as the person takes their own life with no “external assistance,” and those who help the person die must not do so for “any self-serving motive.”

Dr. Willet would later die by assisted suicide in Germany in 2025, reportedly in part due to the psychological trauma he experienced following his arrest and detention.

It’s unclear if Willet was evaluated using the new AI assessment, but Nitschke will apparently include the new test in his latest version of the Sarco that he designed for couples, according to the Daily Mail.

The “Double Dutch” model will evaluate both partners and allow them to enter a conjoined pod so they can pass on to the next life while lying next to each other.

The whole thing does raise a question, though: why do you need AI for this?

They were able to find a psychiatrist for the one use of the pod thus far, and it’s not like they’re doing this at such a volume that they need to pass the assessment off to AI to expedite the process.

Whatever your stance on assisted suicide may be, the inclusion of an AI test over a human assessment feels like it undermines the dignity of choosing to die.

A person at the end of their life deserves to be taken seriously and receive human consideration, not pass a CAPTCHA.

The inventor of a 3D-printed “suicide pod” now wants artificial intelligence to decide who is allowed to use it, shifting one of medicine’s hardest judgments from human hands to software.

Philip Nitschke, long a lightning rod in the right-to-die movement, is pitching Al screening as a way to make assisted dying more consistent and less bureaucratic, even as critics warn it could turn life-and-death decisions into an opaque algorithmic process.

I see his latest proposal as a stress test for how far societies are willing to let Al arbitrate the most intimate human choices.

At the center of the controversy is Sarco, a sleek capsule that promises a peaceful death at the push of a button, and a new generation of devices that add Al “mental tests” and even synchronized deaths for couples.

The technology is arriving faster than the ethical and legal frameworks around it, leaving regulators, clinicians, and ethicists scrambling to catch up.

From Sarco pod to Al gatekeeper

Philip Nitschke built his reputation by pushing the boundaries of assisted dying, and his latest move is to push Al into that space as well.

The original Sarco capsule, a 3D-printed pod that fills with nitrogen to induce hypoxia, was already marketed as a way for people to end their lives without a doctor present, and Nitschke has framed it as a kind of hiqh-tech autonomy for those who want control over their final moments.

In recent interviews, he has argued that an Al system should decide who is eligible to use such a device, replacing traditional psychiatric and medical assessments with automated screening that he believes could be more accessible and less biased, a vision that has put him at the center of a new debate over how far Al should reach into end-of-life care, as highlighted in coverage of Philip Nitschke.

Earlier this year, reporting on the Sarco device described how a “controversial assisted dying device” was being upgraded with Al, underscoring Nitschke’s belief that software can shoulder some of the moral and clinical weight that currently falls on doctors and legal panels.

The pod itself, known simply as Sarco, has been presented as part of a broader experiment in using automation to streamline the path to assisted death, and Nitschke’s insistence that Al should decide who can end their life marks a sharp escalation from using technology as a tool to using it as a gatekeeper.

Al “mental tests” and the Double Dutch upgrade

The most concrete expression of this shift is a new Al-powered mental assessment that would run before the pod can be activated.

In Switzerland, a version of the device has been described as a Swiss suicide pod that adds an Al mental test to judge whether a user is “fit” to proceed, with the system capable of delaying access for up to 24 hours.

Critics quoted in that reporting questioned why Al is needed at all, arguing that Nitschke has also been promoting a new model nicknamed Double Dutch, which he says will integrate the Al software directly into the pod’s workflow.

In one account, he explained that “with the new Double Dutch, we’ll have the software incorporated, so you’ll have to do your little test” before the device can be activated, a description that makes clear the Al is not an optional add-on but a mandatory gate.

Another report on the same upgrade described how the 64-yea old user whose case drew attention last year helped spur Nitschke to formalize these tests, suggesting that real-world controversies are directly shaping the design of the Al checks.

“Die together” pods and the couples’ dilemma

Alongside the Al screening, Nitschke is also promoting a feature that allows couples to die at the same time, a development that raises its own ethical and technical questions.

Reporting on the new Al-powered feature described how the Controversial inventor has designed the system so that two pods can be synchronized, allowing couples who want to die together to activate their capsules simultaneously.

The idea is marketed as a compassionate option for partners facing terminal illness or unbearable suffering, but it also multiplies the complexity of consent, coercion and timing, especially if one’s partner’s mental state is less clear cut than the other’s.

Nitschke has said he has received interest from couples who wish to die together, including at least one pair who contacted him through UK media, and he has framed the Al checks as a way to ensure each person independently passes a mental test before the device can be activated.

Coverage of these plans noted that the announcement has reignited debate over whether such devices could still attract criminal charges, even in jurisdictions with permissive assisted dying laws, and that the “die together” concept has put Sarco back in the spotlight as a symbol of how far right-to-die technology might go, as detailed in reports that quoted Speaking Nitschke on the renewed scrutiny.

Bioethics: Three scenarios for Al at the end of life

What Nitschke is proposing does not exist in a vacuum, and bioethicists have been sketching out how Al might fit into end-of-life decisions more broadly.

One influential analysis laid out Three Scenarios for in End of Life Decisions, ranging from Al as a decision-support tool that helps clinicians interpret complex data, to Al as a co-decision-maker that shares responsibility, and finally to Al as an autonomous decider that effectively replaces human judgment.

Nitschke’s vision of an Al that decides who can enter a suicide pod clearly leans toward that third scenario, where software is not just advising but ruling on eligibility.

In that framework, the key questions are about accountability and error: if an Al system wrongly approves or denies a request for assisted death, who bears responsibility, and how can such mistakes be detected and

Law, medicine, and the next assisted-dying device

For lawmakers and clinicians, the arrival of Al-equipped suicide pods forces a collision between emerging technology and existing assisted dying frameworks.

Traditional laws in places that allow euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide typically require human doctors to assess capacity, confirm diagnoses, and document consent, processes that are slow and heavily regulated.

By contrast, Nitschke’s devices are pitched as consumer-facing products that can be activated after an automated mental test, a model that could sidestep established safeguards and leave regulators scrambling to decide whether such pods fall under medical, consumer, or entirely new categories of oversight, a tension that has been noted in coverage of the Creator of the New Assisted Dying Device.

At the same time, the broader medical community is wrestling with how to integrate Al into end-of-life care in ways that support, rather than replace, human judgment.

The AI-powered access keypad as seen on the Sarco at Venice Design, 2019

Some clinicians see potential in using Al to flag patients who might benefit from palliative care earlier, or to help standardize capacity assessments, but they generally stop short of endorsing fully automated decisions about who may die.

Nitschke’s insistence that Al should decide who can end their life, and his move to embed that logic into Sarco, Double Dutch, and other New Assisted Dying Device concepts, pushes the conversation to an extreme that many ethicists regard as an “ethical disaster waiting to happen;’ as reflected in critical coverage of Nitschke and his Al-powered suicide chamber.