December 18, 2025

He pioneered the Right to Die movement but thought it didn’t go far enough

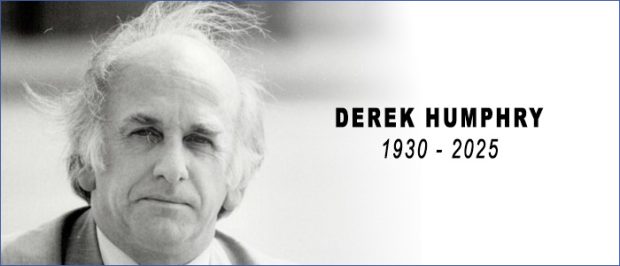

Derek Humphry

He pioneered the Right to Die movement but thought it didn’t go far enough. By Katie Engelhart

The book was slim and to the point.

There was a chapter on how to kill yourself with pills and a plastic bag, and another on death by starvation.

Also sections on electrocution, hanging and poisonous plants.

The author promised, in an interview, straightforward “instructions for a perfect death, with no mess, no autopsy, no post-mortem.” And he urged his readers to be cleareyed about what was to come.

“This is the scenario: You are terminally ill, all medical treatments acceptable to you have been exhausted,” the book read.

“The dilemma is awesome. But it has to be faced. Should you battle on, take the pain, endure the indignity and await the inevitable end, which may be days, weeks or months away?

Or should you take control of the situation … ?”

By the time he wrote that book, “Final Exit,” Derek Humphry had been a prominent Right to Die campaigner — sometimes called the founding father of the movement — for over a decade.

Still, when he tried to find a publisher for his book, he couldn’t.

Nobody, it turned out, really wanted to publish a suicide manual — or what its author called a guide to “self-deliverance.”

So Humphry got Hemlock to print the book in 1991 and started handing out free copies around Los Angeles.

He was as surprised as anyone when, later that year, the book made its way onto the New York Times best-seller list and stayed there for 18 weeks, eventually selling over one million copies.

Commentators described the book’s success as an indictment of the medical profession: of doctors whose duty to heal had, in recent years, become a compulsion to prolong life at all costs.

The people who bought “Final Exit” were afraid of dying badly, of dying slowly, of dying in a hospital, hooked up to machines.

Humphry’s introduction to assisted death came in the early 1970s, when he was still living in his native England.

His first wife and the mother of his three sons, Jean, had discovered a lump in her breast.

Later the cancer metastasized.

Jean didn’t want to die slowly and in pain, the way her mother had, and she asked her husband to help her find another way.

Two years later, on an afternoon in March, Humphry made Jean, who was just 42, a cup of coffee laced with painkillers and sleeping pills.

She drank it and died quickly, which was a relief to Humphry, who worried that the medications would fail and that he would have to suffocate his wife with a pillow.

Soon after, Humphry moved to Santa Monica, Calif., and started the Hemlock Society, one of the country’s first Right to Die advocacy groups, named for the poison that Socrates drank in ancient Athens.

This was the 1980s. It was the time of Ronald Reagan, of Jerry Falwell, of the so-called Moral Majority.

“My God,” someone cried out at an early meeting organized by Humphry.

“They firebomb the houses of pro-abortion people. … What do you think they’ll do to us?”

Over the next decade, Humphry opened 80 chapters and enrolled around 45,000 members who raised money to fund Death With Dignity ballot initiatives in a handful of states.

But then a decade passed, and all of Hemlock’s efforts had come to very little. And Humphry, in turn, had grown impatient with his own creation.

It was, in part, that everything was moving too slowly; after all those years, physician-assisted death was still illegal everywhere.

Also, legal change didn’t seem to be what Hemlock’s rank and file really wanted right now. Humphry had noticed that at chapter meetings, members seemed less interested in consciousness-raising than they were about the practicalities of how to die painlessly.

The people with AIDS especially wanted specific instructions: What pills? How many?

These people knew that it wasn’t always easy to die. Some deaths were agonizing. Some took hours and left panicked bystanders to resort to guns or pillows.

Others were violent and left a mess behind. Some people tried to end their lives only to wake up feeling worse off than before.

In small members-only seminars, and later in brash public gatherings, Humphry instructed attendees on what he claimed were more foolproof methods.

By 1994, when Oregon passed the Death With Dignity Act, the world’s first law permitting physician-assisted dying, Humphry was disenchanted with the political process he had helped to set in motion. The Oregon law was so much narrower — so much less radical — than he had hoped.

It applied only to people who were terminally ill and within six months of a natural death — people who were going to die soon anyway.

It did nothing for so many other people who were suffering: those with degenerative conditions like multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s; those with spinal cord injuries and paralysis; those with unrelenting chronic pain.

Also it left so much power in the hands of the medical profession and its bureaucracies. It meant that dying people had to beg for approval from their doctors to be allowed to stop living.

Humphry and the larger movement parted ways.

Humphry left Hemlock, which, in the early 2000s, merged with another group and then splintered.

The largest faction reconstituted itself as Compassion & Choices, an advocacy group with an eight-figure annual budget committed to passing Oregon-style laws in other states. (Medical Aid-in-Dying is now legal in 12 American jurisdictions.)

Later, Compassion & Choice’s founder would dismiss Humphry’s plastic-bag method as “sort of the end-of-life equivalent of the coat hanger.”

Humphry retreated to a small house near Eugene, Ore., by the Willamette River.

He continued advocating and writing and, from time to time, published revised editions of “Final Exit,” updating drug doses and adding a new section on inert gas canisters.

In earlier editions of the book, Humphry had included his personal phone number; he still got a call or two from readers almost every day. Most of them were dying and were scared.

One might have expected Humphry to “self-deliver” — particularly when he started to experience more symptoms of congestive heart failure.

He did consider it, and friends say he had “a stash of a lot of stuff” to use.

But his wife, Gretchen, explained that her husband ended up in the hospital and then was transferred to hospice, where his organs began to fail and where he died a so-called natural death.

In the end, she said, he was comfortable enough to hold on.

Katie Engelhart is a contributing writer for the magazine. She received a Pulitzer Prize in 2024 for feature writing.